The Marrow of Family

A single father discovers how far the heart can stretch when he adopts his second son.

by

“TELL HIM TO GO HOME!” THE JUDGE SCREAMED into the telephone. “Tell him I will not-I will not-allow a single man to adopt a Ukrainian child.”

I had traveled 4,287 miles from Bangor, Maine, to this Ukrainian orphanage on the shores of the Black Sea. That’s where I had met Anton, the five-year-old boy with the dark curls and brown eyes, and had decided that I wanted him to be my son. But the judge would have none of it.

How could this be? After all, I had adopted before, eight years ago. That experience had brought me Alyosha, a blond seven-year-old from Russia with a million-dollar smile. Didn’t my raising him all these years give me a track record as a responsible father? How on earth could this judge dismiss me on the basis of marital status alone?

The judge’s antipathy reminded me that adopting Alyosha had also not been easy. I had endured three years of complications, dead ends, and bitter frustrations-all worthwhile in every way.

By the time Alyosha turned fourteen I had found that his increasing independence had freed up a sort of emotional space in our home. He needed less “hands on” parenting as the years progressed, but I felt, at the age of forty-five, that I still had the energy, disposition, and desire for family building. Further, I loved having the “sense” of a child in the house-the footfalls, comings and goings, and unmatched socks -and was not ready to say goodbye to that landscape.

And so, one evening, in a quiet moment, I asked my son if he’d ever thought about having a little brother. Alyosha paused for a moment, then placed his hand on my shoulder. “Dad,” he said, “don’t you think it works just fine with the two of us?”

I smiled and nodded. Indeed, I had always considered Alyosha to be the perfect only child-active and happy, with a healthy capacity for solitude and quiet time.

So I was surprised a year later when Alyosha raised the issue of another adoption: “Dad, I’ve been thinking. Maybe it would be a good idea to get another kid.”

I asked him why the change of heart. “Well,” he said, “so you won’t be lonely when I’m gone.”

I explained that adoption wasn’t like groceries: when one can is emptied you buy another so the shelf will always be full.

Still, Alyosha had resurrected something for which we both seemed prepared. We agreed that what we were looking for was a boy five or six years old. “You will have your big-boy world, and he will have his little-boy world,” I told him. “You’ll be able to love each other without getting in each other’s way.” I gave my adoption agency a call and learned they were having great success with Ukraine.

Everything went without a hitch. But I had missed one significant detail. Unlike other countries, Ukraine did not offer advance information on adoptable children, so an immense leap of faith was in order. As far as Ukraine was concerned, nothing would happen until I actually went there.

My head began to swim with doubts and what-ifs. Would there be children in the age range I was approved for? Would I be pressured to adopt a particular child? If it didn’t work out, would I lose thousands of dollars in fees, much of it borrowed? And yet I felt compelled to go forward. After the initial paperwork, the home study, and the lion’s share of the costs have been paid, jumping ship is unthinkable.

THE CALL TO TRAVEL came in early September 2001, after the start of my teaching semester, and I scrambled to make arrangements for my students, have someone look in on the house, and, most important, care for Alyosha.

I left for Ukraine by way of Poland in late September. Once in Warsaw I boarded a night train for Kiev. The train wheezed and clanked every mile of the way, as if being pulled against its will through the frigid night. The sun rose on a landscape of sad poverty: At all stops, wan children and mothers carrying babies came to the windows to beg.

After eighteen hours I arrived in Kiev, which was alive with the sights and sounds of construction, as if most of the nation’s scant resources were dedicated to making a showplace of the capital.

The next morning I was picked up by a member of the Ukrainian adoption group. Katya was young, swank, and animated, speaking almost impeccable English. She whisked me to the Adoption Center-the starting point for all Ukrainian adoptions.

We entered. Katya slipped a child’s profile before my eyes. “This one,” she said in a harsh whisper. “He’s the best. A wonderful boy.”

I threw her a smile. “How do you know that?”

“Take it from me.”

I beheld a picture of a little boy with big brown eyes and wild, curly brown hair who looked absolutely terrified. “No,” I quietly said. “This boy doesn’t speak to me. I don’t know why, but I don’t connect with him.”

My response seemed to frustrate Katya. She pursed her lips as I began to leaf through other files. Document after document told stories of lament, abuse, and abandonment. Every so often I glanced sidelong at Anton’s big brown eyes. “Okay, I’ll visit him,” I told Katya, “but I’m not promising to adopt him.”

WE SET OFF for the twelve-hour train ride to the Black Sea village of Ochakiv, passing through a flat landscape of black soil, great stretches of overcast sky, and crumbling villages. When we got to the orphanage there was no evidence that this was a place that housed children. Silence reigned.

Once inside, however, I was impressed by the cleanliness, the brightly painted walls, and the light that cascaded through immense windows. Lydia, the director of the so-called “Detskiy Dom” (Children’s Home), was a woman of about fifty, whose stately bearing and deep, resonant voice were reminiscent of Kathleen Turner.

We were joined by Valentina-a fortyish child-welfare advocate with a copper beehive of hair and a smear of blood-red lipstick; her clerk Ludmila, and Svetlana, an imposing, white-smocked pediatrician in her sixties. They all spoke glowingly of the frightened boy in the photo.

“One thing,” Lydia added after singing his praises. “Three other families have come to visit Anton in the past year. In each case, he screamed and cried and the families changed their minds. So be prepared.”

I moved to the doorway and watched as Anton-so tiny!-was led in by his caretaker, “Mama Taia.” His chin was plastered to his chest and I sensed his emotional fragility. I got down on the floor, so that I would be looking up to-rather than down upon-him.

Anton’s hair had been shorn of its curls, and he blinked his long lashes at me. I took a small toy car from my pocket and handed it to him. Anton joined me on the floor and for the next twenty minutes we played-a rhythmic, almost silent back-and-forth of the little toy, our only connection at the moment.

Finally Lydia remarked, “I’ve never seen this before. He’s not crying.”

I asked if I could observe Anton with his group. He took my hand and led me to a large sunroom where three other boys and three girls were playing on a carpet. Anton joined them, became chatty and animated, and shared his car. A little while later we were back in Lydia’s office and Anton was sitting on my lap, still fingering his toy.

“He likes you,” she said as I stroked his head. “Maybe you’d like a couple of days to think about it.”I looked down at Anton, felt his warmth against me, and took renewed notice of the sparkle in his soulful eyes. “Lydia,” I said, “I don’t need a couple of days. I can think of no reason not to adopt this little boy.”Before my arrival in Ukraine I had harbored a nagging fear that I would somehow return with the “wrong” child. That sense had evaporated. I knew, in my marrow, that Anton was meant to be my son and Alyosha’s little brother.

AND THEN THE JUDGE WEIGHED IN. Everyone was shocked when she began making calls-to Lydia, Valentina, and others-directing them to discourage me. She could not envision allowing a single person-much less a single man-to adopt. She had never permitted it, and she was not about to start.

All of the Ukrainian women who had aligned themselves with my cause went to bat for me. They called the judge, they visited her, they brought her gifts. Then my adoption representatives in Kiev got involved. They appealed to the regional judge, they sent the Ochakiv judge case studies of successful single adoptions, they convinced a leading prosecutor to contact her.

Finally, in a moment of what must have been exquisite duress, she cried out-loud enough for her secretary to hear and convey to us- “The pressure is unbearable!”

I was granted my court date. When I stood before the judge, she did not look so fearsome, although she avoided eye contact with me. The judge relayed her questions through my translator. “Why,” she asked with annoyance, “do you want another child? You already have one.”

I explained that there are only two reasons why families grow: by accident or by design. Wasn’t it a wonderful thing, I asked rhetorically, that I had thought so deeply about a second son?

The women of Ochakiv who had accompanied me made eloquent pleas on my behalf-relating tales of personal poverty, their experiences with foreign families hoping to adopt, and their aspirations for the orphan children of Ochakiv. It wasn’t long before nearly everyone in the courtroom was in tears. The judge herself finally removed her glasses, wiped her eyes, and pronounced, “Mr. Klose, it is clear that you have stolen every heart in this courtroom-including mine.”

Miraculously, she approved the adoption. Flush with my triumph, I returned to the orphanage, where Anton was hob-nobbing with his peers in their activity room. He came over and rested his head against my shoulder.

As we prepared to leave, I distributed trinkets I had brought for the children, and they presented me with a cassette tape of songs and poems they had made. While Anton stood quietly in his bubble of embarrassment, the little girls lined up to buss him on the cheek. Then the boys shook his hand. After a final, group wave, the children were sent off to bed. Then the caretakers said their goodbyes before ushering Anton into my waiting arms.

THE TRIP BACK TO MAINE took twenty-one hours, most of which Anton slept away. As I looked down at his head lying serenely in my lap, I wondered at the trust and affection this little boy was showing me after such short acquaintance. Yes, I made a leap of faith in coming to Ukraine; but it was nothing compared to the one Anton had made in allowing me to take him from the only world he had ever known. And while I was thinking this his small hand, which held my finger, gave it a gentle, reflexive squeeze.

Like Alyosha before him those eight brief years ago, Anton took to his new environment with alacrity and a desire to explore. He simply seemed happy to be here, his innate energy unlocked by all that was new and unfamiliar. By his second week he was nestled among his kindergarten cohort. When a visiting friend remarked, “He’s a normal five-year-old boy,” I felt as if she had bestowed the highest of compliments, as if normalcy were some state of perfection to aspire to.

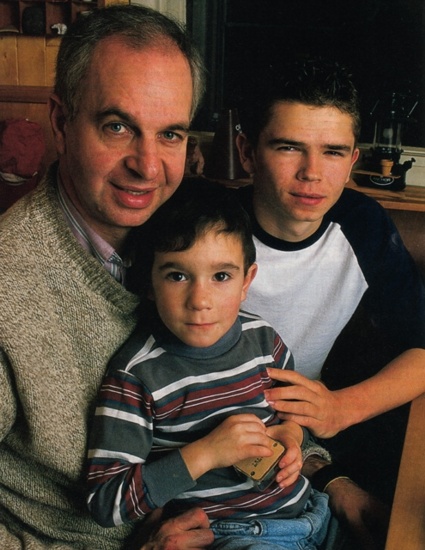

Most satisfying, perhaps, is his relationship with Alyosha. If ever I had any doubts about how they would get along, they dissipated almost upon Anton’s arrival. Anton looked up at his tall, strong, handsome brother as if contemplating one of the wonders of the world, and Alyosha, for his part, was soon treating Anton as if he had lived with us all his life.

Does Anton still seem new to me? Absolutely. But I already sense the coming of the day when I will be able to say, as I did with Alyosha, that I don’t feel that I adopted Anton at the age of five and a half. I feel instead that I have raised him all his life but somehow misplaced the baby pictures.

Robert Klose is an associate professor of biological sciences at University College of Bangor, Maine and the author of Adopting Alyosha: A Single Man Finds a Son in Russia.

Pull Quote:

“Yes, I made a leap of faith in coming to Ukraine; but it was nothing compared to the one Anton had made in allowing me to take him from the only world he had ever known.”

This article originally published in HOPE magazine

Photo is courtesy of Peggy McKenna